Lajaren Hiller at the Experimental Music Studio

No area of computing holds more interest to me personally than computer music. For years I’ve been fascinated with everything from the work of Lejaren Hiller at the Experimental Music Studio to Brian Eno’s generative music. While many see the changes computers brought to production and performance as the more impressive innovations, computers as composers offers incredible possibilities that are only now beginning to come to light.

One of the great names in the history of computers as composers is Prof. David Cope; the Dickerson Emeritus Professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz. Cope began as a traditional musician and composer, creating hundreds of works performed around the world. 1982’s American Record Guide said of Cope, “David Cope is unquestionably one of this generation’s most ambitious, prolific and multifarious composers.” His works exemplify what the most ambitious composers of the 1970s and ‘80s brought to life and his Concert for Piano and Orchestra is seen as one of the most impressive works of avant grade music of the last forty years.

His attention was drawn to computers in the 1970s. “Part of me has always been that algorithmic side.” Professor Cope said when I interviewed him this March. Cope studied computing, learning programming techniques and studying artificial intelligence. He also began to find ways to apply it to his musical work. He even used an IBM computer and punched cards to compose a short piece of music.

“This is 1975, and it took [an] enormous amount of time to program and a very long time to actually get the results out, because the cards that we received an answer, in response to the input, had to be converted from those little holes in the punch cards to actual little physical notes on a page. But it succeeded — at least in getting performed.” Professor Cope mentioned in an interview with engadget.com, adding, “It was an awful piece, just truly dreadful.”

He later attended the Summer Workshop in Computer Music at Stanford, and studied several computer languages, including LISP, the standard programming language for artificial intelligence work.. He also began teaching the Workshop in Algorithmic Computer Music at the Digital Arts Research Center at UC Santa Cruz.

In the early 1980s, Cope had a commission for an opera, but was dealing with a serious case of composer’s block. Like many artists when facing a deadline, Cope procrastinated by beginning a new project, in this case, working on a music composition program.

“I decided I would just go ahead and work with some of the AI I knew and program something that would produce music in my style. I would say ‘ah, I wouldn’t do that!’ and then go off and do what I would do. So it was kind of a provocateur, something to provoke me into composing.” Cope said.

The program he started working on would eventually become known as Experiments in Musical Intelligence, also known as EMI or Emmy.

“Experiments in Musical Intelligence is an analysis program that uses its output to compose new examples of music in the style of the music in its database without replicating any of those pieces exactly.” he noted.

Tech Closeup: Music Professor David Cope

The program would analyze music Cope had entered enter into EMI’s database, and that input would be used to direct the composition of new works in the same style.

“I couldn’t figure out what my style was, so I suddenly started to say ‘well, I don’t know what my style is, so I should figure out what style is, period,’” Cope said, “I had to work something out, so I developed this program, my first in a long line of programs that are what I called ‘data-driven,’ that work on the basis of data alone, and not on my thoughts of what they should produce … thoughts that arise from the analysis of data.”

Cope entered the work he had begun into EMI and began to use the program to create new works using this data-driven approach, what could be called EMI’s “style.” As he used it to create new pieces, he began to notice patterns in his own work that he had never caught before, and based on those observations, began to change his own style.

“I looked for signatures of Cope style. I was hearing suddenly Ligeti and not David Cope.” the composer noted, “As Stravinski said, ‘good composers borrow, great composers steal’. This was borrowing, this was not stealing and I wanted to be a real, professional thief. So I had to hide some of that stuff, so I changed my style based on what I was observing through the output [of] Emmy, and that was just great.”

Cope successfully used EMI to break his composer’s block, and assist in the composition of his opera. The entire process took eight years.

“Actually, it took about two days, once I got the program done, but it was eight years from the commission to the actual premiere on the East Coast.”

Finished with his opera, Cope set EMI to compose new works in the style of various legendary composers. He would enter significant portions of a composer’s music into the system, and then use it to create new works using their style.

“When I first started working with Bach and other composers I did it for only one reason – to refine and help me understand what style was. No other reason. When I started to play this stuff for faculty and some friends of mine, they would say ‘hey, that’s not bad, it might fool someone if it was played by actual human beings. So, I took that seriously, and realized that at least as far as my promotions were concerned at the university, if I was going to do all this programming, I needed to publish something.”

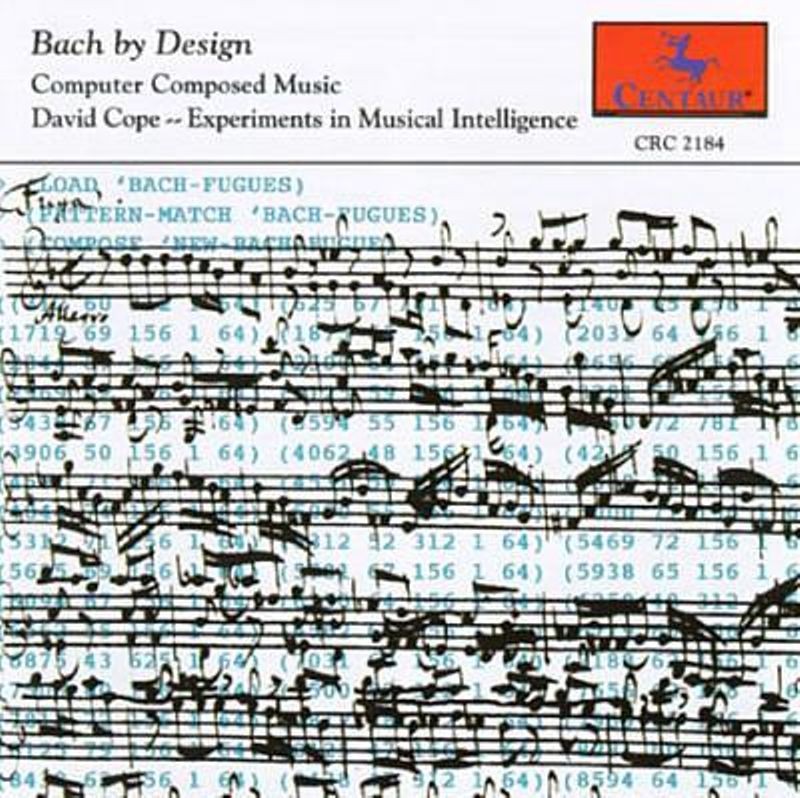

Bach by Design (1997) from Centaur Records

Cope wrote several books, and began to collect and record EMI’s compositions. Bach, with a massive number of surviving works and an easily identifiable style, was a natural choice for Cope to start EMI’s recording career. Cope compiled EMI’s compositions in the style of Bach, as well as in the form of Bartok, Brahms, Chopin, Gershwin, Joplin, Mozart, Prokoviev, and even David Cope. These formed the album Bach by Design. Producing the album was the easy part; getting it released was the hard part.

“I spent almost a year trying to get an actual record company to produce the music. It was really tough.” Cope said, “I remember my greatest exasperation was, coming in on the same day, were two negative replies. The first said ‘we only publish contemporary music, and this, by our definitions, is not contemporary music, and then the other one said ‘we only do classic music, and this is not classical music’, so I said ‘then, what is it?’”

Eventually, Cope managed to get Centaur records to produce the album, but he faced another problem – getting human players!

“Then I tried to get a human performer to do it, and the fingering wasn’t easy or some such, so I gave up and had a Disklavier play it.”

The Disklavier, a form of piano that uses sensors and solenoids to reproduce the performance of actual piano playing, performed the works composed by EMI. This would make Bach by Design one of the first albums produced with no humans composing or performing the music. The choice to perform the music via Disklavier led to other negative reactions from critics.

“The first three reviews of Bach by Design were negative on the basis that it sounded so stiff, and when I read the reviews, I was very upset that they weren’t primarily about how (the pieces) were composed, they were primarily about how they were performed.”

Tech Closeup: Music Professor David Cope

Despite the critical reactions, the pieces EMI composed were certainly Bach-like. Professor Douglas Hofstadter of the University of Oregon organized a musical form of the Turing Test. Pianist Winifred Kerner performed three pieces in the style of Bach: one written by EMI, one by Dr. Steve Larson, and the last an actual piece by Bach. The audience then had to attempt to tell which piece was which. The audience selected Emmy’s piece as the actual Bach, while believing that Larson’s was the one composed by computer.

“Bach is absolutely one of my favorite composers,” Dr. Larson said to the New York Times, “my admiration for his music is deep and cosmic. That people could be duped by a computer program was very disconcerting.”

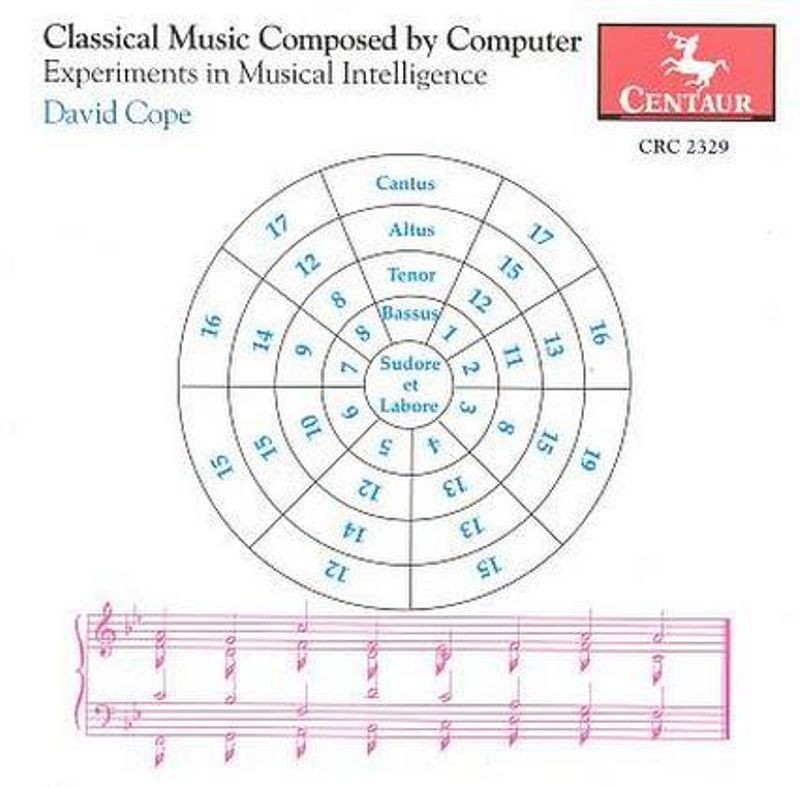

Classical Music Composed by Computer

For the next recording, Classical Music Composed by Computer, Cope used human musicians to play the pieces composed by EMI. These works, in the styles of Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Cope, Joplin, Mozart, Rachmaninov, and Stravinsky, were performed by musicians including Cope’s wife Mary Jane, and a Balinese gamelan orchestra interpreting a piece in the style of Bach. The album received better reviews and caught the attention of many in both the classical music and artificial intelligence communities. These pieces showed that Emmy could produce works of surprising depth and range.

“EMI forces us to look at great works of art and wonder where they came from and how deep they really are,” Hofstadter said to the New York Times. “Nothing I’ve seen in artificial intelligence has done this so well.”

Cope produced several more albums using EMI, including Virtual Mozart and Virtual Rachmaninov. EMI even composed a complete symphony in the style of Mozart which was performed at the Santa Cruz Baroque Festival in 1997. Cope has produced thousands of other works in various styles using EMI, including 5,000 Bach chorales available on his website. These pieces composed by Emmy challenged many notions, not only about musical style, but of how computers can be used within the arts as a whole. EMI produced music that could fool some of the most knowledgeable classical music fans, but at the same time it relied on the input of existing works.

“I find myself baffled and troubled by EMI,” Hofstaeder noted. “The only comfort I could take at this point comes from realizing that EMI doesn’t generate style on its own. It depends on mimicking prior composers. But that is still not all that much comfort. To what extent is music composed of ‘riffs,’ as jazz people say? If that’s mostly the case, then it would mean that, to my absolute devastation, music is much less than I ever thought it was.”

Cope’s work with EMI and follow-up programs such as Alena and Emily Howell, along with work like Harold Cohen’s AARON paint system, naturally raise the question ‘are computers creative?’ When I asked Cope about whether he believed computers were creative, I was taken aback by his view.

“Oh, there’s no question about it. Yes, yes, a million times yes. Creativity is simple; consciousness, intelligence, those are hard.”

5000 works by EMI available as MIDI files