Late one afternoon in the fall of 1974, in the sleepy California seaside town of Pacific Grove, programmer Gary Kildall and electronic engineer John Torode “retired for the evening to take on the simpler task of emptying a jug of not-so-good red wine … and speculating on the future of our new software tool”. [1] By successfully booting a computer from a floppy disk drive, they had just given birth to an operating system that, together with the microprocessor and the disk drive, would provide one of the three fundamental building blocks of the personal computer revolution. While they knew it was important, neither realized the extraordinary impact it would have on their lives and times.

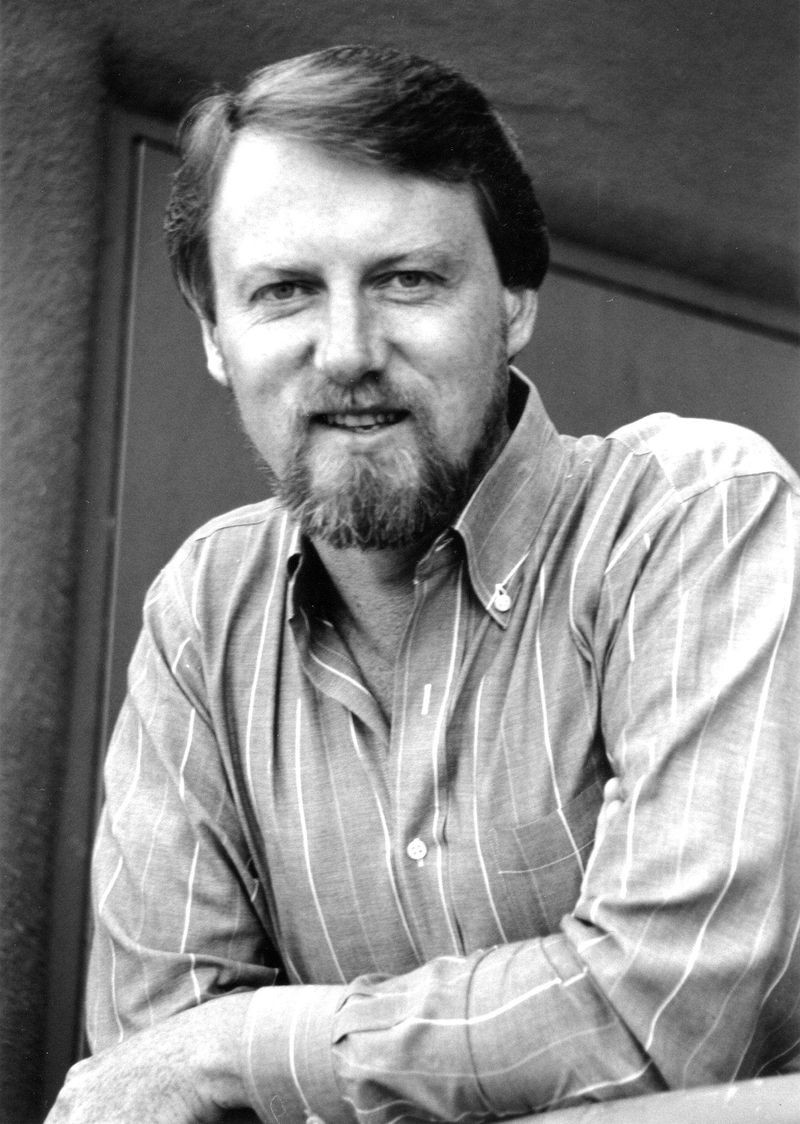

Gary Kildall in 1988 Photo: Copyright Tom O’Neal, Carmel Valley, CA

Gary Arlen Kildall was born to a family of Scandinavian descent in Seattle, Washington in 1942. His inventive skills flourished in repairing automobiles and having fun, but suffered in scholastic pursuits. He qualified for admission to the University of Washington based on his teaching experience at the family owned Kildall Nautical School rather than his high school grades.

In 1963, Kildall entered college and married his high school sweetheart Dorothy McEwen, who supported him in his studies. He was one of 20 students accepted into the university’s first master’s program in computer science. Here his mathematical talents were applied to a subject that fascinated him, all-night sessions programming a new Burroughs B5500 computer. To avoid the uncertainty of the draft at the height of the Vietnam War, on graduating with a PhD he entered a U. S. Navy officer training school and was posted to serve as an instructor in computer science at the Navy Postgraduate School (NPS) in Monterey, California.

Kildall remained at NPS as an associate professor after his tour of duty ended in 1972. He became fascinated with Intel Corporation’s recently introduced 4004 microprocessor chip and simulated its operation on the school’s IBM mainframe computer. This work earned a consulting relationship with Intel where Hank Smith of the Microcomputer Systems Group commissioned the development of PL/M, a high-level Programming Language for Microcomputers that served the company for decades.

To enable software development for Intel’s second generation 8-bit device, the 8080, Kildall needed to connect the chip directly to a new 8” floppy disk-drive storage unit from Memorex. Using PL/M, he wrote the prototype code for his Control Program for Microcomputers (CP/M) in a few weeks. (It was later tuned and rewritten in 8080 assembly language.) His own efforts to build the complex electronic circuitry required to physically transfer the data failed and the project languished for a year. Frustrated, he called John Torode, a college friend then teaching at U.C. Berkeley, who crafted a “beautiful rat’s nest of wirewraps, boards and cables” for the task.

Working in the tool shed behind his home in Pacific Grove, Kildall “loaded my CP/M program from paper tape to the diskette and ‘booted’ CP/M from the diskette, and up came the prompt: *. This may have been one of the most exciting days of my life, except, of course, when I visited Niagara Falls,” [2] he exclaimed, “We now had the power of an IBM S/370 [mainframe computer] at our fingertips.” [1] This is going to be a “big thing” they told each other. There is no record of the precise date of this event, but Torode recalls that it was before he moved to Chicago in the fall of 1974. [3]

As Intel expressed no interest in CP/M, Kildall was free to exploit the program on his own. Torode refined the “rat’s nest” and produced a complete floppy disk controller system. The first commercial licensing of CP/M took place in 1975 with contracts between Torode’s company, Digital Systems, and Omron of America. Kildall continued teaching part time at NPS and in 1976, with his wife Dorothy as co-founder, they established a company called Intergalactic Digital Research. They shortened the name to Digital Research Inc. (DRI) after a couple of years.

Glenn Ewing, a former NPS student, approached DRI with the opportunity to license CP/M for a new family of disk subsystems for microcomputer maker IMSAI, Inc. Reluctant to adapt the code for another controller, Kildall worked with Ewing to split out the hardware dependent portions so they could be incorporated into a separate Basic Input Output System (BIOS). This allowed all 8080 and compatible microprocessor-based computers to run same the operating system on any new hardware with trivial modifications that could be accomplished by the designer in a couple of hours.

According to John Wharton, Intel’s technical liaison to DRI who became a DRI contractor and a friend of Kildall, this was “perhaps Gary’s most profound contribution … All previous computer software had targeted specific hardware environments. Gary isolated the system specific hardware interfaces of his OS within a set of “basic I/O system” routines, so it and all applications code would be fully machine independent. This idea created the third-party software industry by expanding the potential market several orders of magnitude.” [4]

Gordon Eubanks, who was a student of Kildall’s at NPS, identifies another significant contribution: “While I think separating out the BIOS was very important, to me the actual breakthrough was the dynamic relocation of the OS so it could run at high memory on any size system with at least 16K of RAM. I met with him the morning after he figured out how to do this and he was floating.” [5]

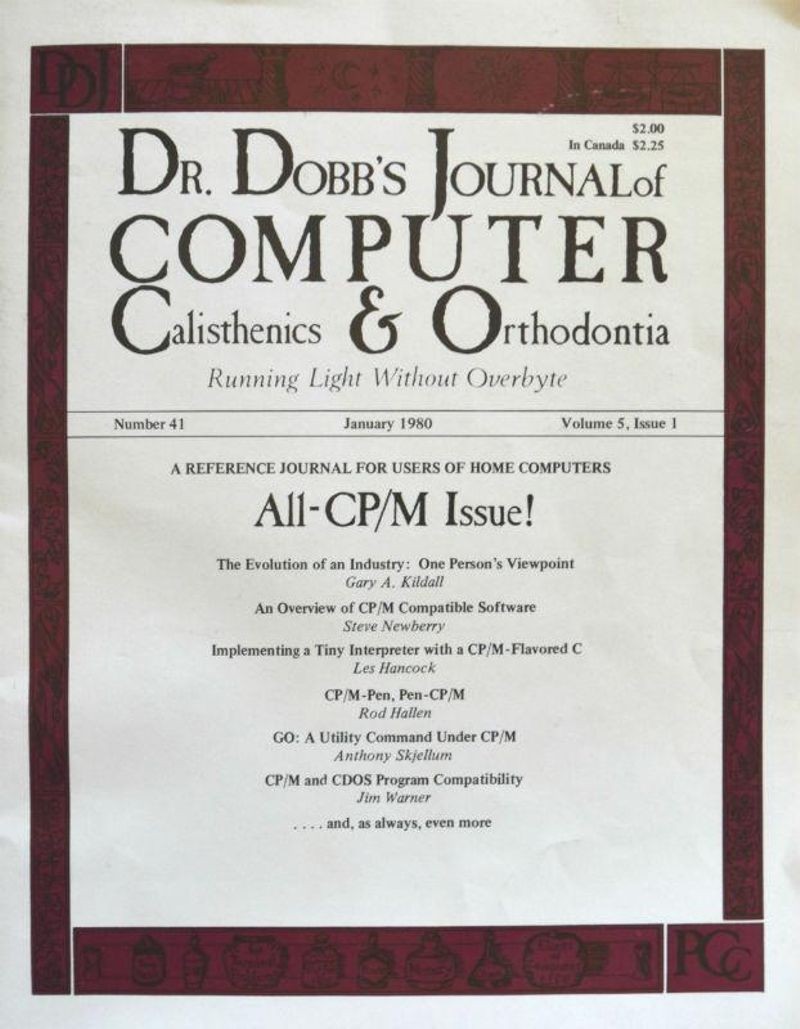

Dr. Dobbs Journal, “All-CP/M Issue!” January 1980. Copyright: Dr Dobbs (www.drdobbs.com)

With the release of CP/M version 1.3, customers responded to articles such as “Upgraded CP/M floppy disc operating system now available” published in the magazine Dr Dobbs’ Journal of Computer Calisthenics and Orthodontia in late 1976 by purchasing disks at $70 per copy. According to Kildall, “In the months that followed, the nature of the computer hobbyist became apparent … CP/M gradually gained popularity through a ‘grassroots’ effect.” [1]

A licensing deal concluded with IMSAI bestowed credibility across the industry. CP/M became accepted as a standard and was offered by most early personal computer manufacturers, including pioneers Altair, Amstrad, Kaypro, and Osborne. With a SoftCard, a Zilog Z80 microprocessor -based add-in card built by Microsoft, it also ran on the Apple II to enable popular applications such as Word Star and dBASE that were originally written for CP/M. Microsoft licensed CP/M from DRI to re-sell with the card.

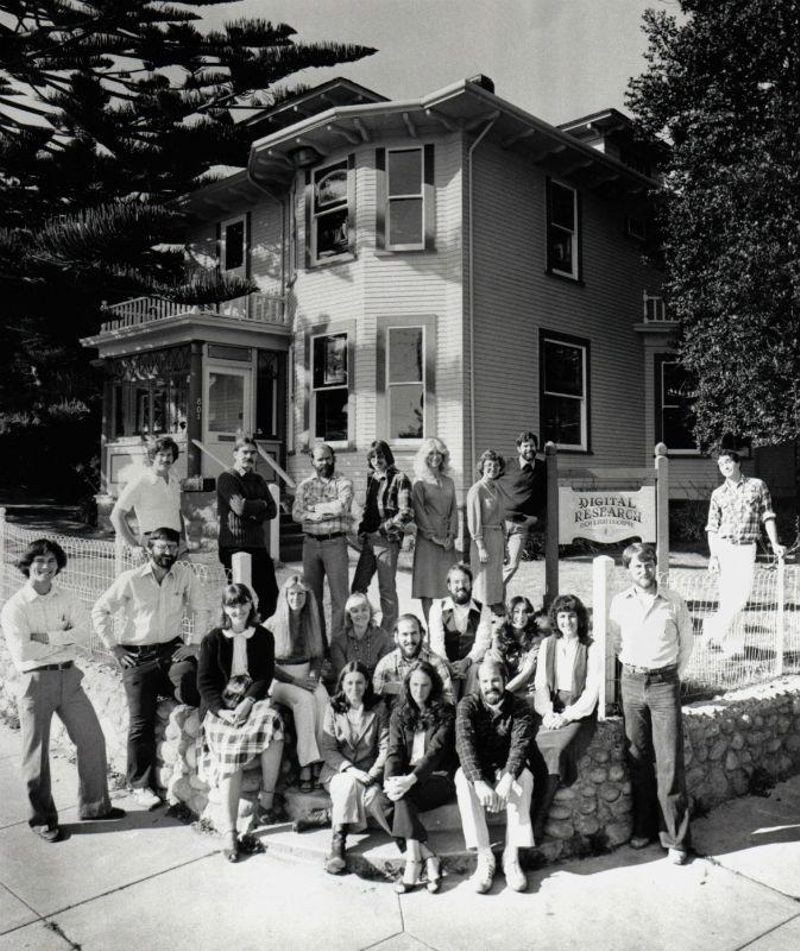

In 1978 Dorothy and Gary purchased a Victorian house on Lighthouse Avenue in Pacific Grove and converted the spacious two-story residence into their company headquarters. One of their first recruits, Tom Rolander joined from Intel in 1979 and immediately set to work writing MP/M, a compatible multi-tasking version of CP/M.

By 1980 DRI employed more than 20 people and Fortune magazine reported that the company generated revenue of $3.5 million. [6] The same article noted that Microsoft earned about the same total over the prior 5 years combined, some of these sales being derived from reselling CP/M licenses. By 1982 DRI disclosed annualized sales in excess of $20 million and that “More than a million people are now using CP/M controlled systems.” [7]

DRI staff outside the headquarters office, Pacific Grove CA, November 1980. Photo: Copyright John Pierce

In 1980 Rod Brock, owner of Seattle Computer Products, had developed a system using the 8086, a powerful new 16-bit microprocessor from Intel. Impatient for CP/M-86, DRI’s promised upgrade for the new chip, his programmer Tim Paterson filled the gap by writing an operating system known initially as QDOS (Quick and Dirty Operating System) and later called 86-DOS. According to Paterson “if there had been a CP/M for the 8086 microprocessor, 86-DOS would never have been developed.”

“I used the 1976 CP/M Interface Guide for my description of the requirements.” To help developers port their software products from the 8080 to the 8086, “I also provided some similar commands from the console,” said Paterson. “So 86-DOS generally had all the same application visible elements as CP/M—the function codes, the entry, point address, part of the File Control Block layout, etc.” [8] He had written his operating system to emulate the ‘look-and-feel’ of CP/M.

In July 1980, IBM assigned Philip “Don” Estridge to develop a desktop computer for the mass market. To get the IBM PC, as it became known, to market as quickly as possible, he used commercially available components, including the Intel 8088 (a lower-cost version of the 8086). When an IBM procurement team visited Bill Gates in Redmond, Washington to license Microsoft’s BASIC interpreter program he referred them to DRI for an operating system.

When the IBM team arrived in Pacific Grove they met with Dorothy and worked with company attorney Gervaise “Gerry” Davis to settle the terms of a non-disclosure agreement. Gary, who had flown his aircraft to Oakland to meet an important customer, returned as scheduled to discuss technical matters. The meeting ended in an impasse over financial terms. IBM wished to purchase CP/M outright, whereas DRI sought a per-copy royalty payment in order to protect its existing base of business. With some alternative approaches in mind, Kildall tried to renew the negotiations a week later but IBM did not respond.

In the meantime, Gates negotiated terms to purchase 86-DOS from Brock. He then sold a one-time, non-exclusive license to IBM, who used the designation PC DOS, but retained the right to license the product as MS-DOS to others. When Kildall discovered that the function calls of the programmer’s application interface were identical to those of the CP/M Interface Guide that was copyrighted and marked “Proprietary to Digital Research” he threatened IBM with a lawsuit.

Kildall and Davis negotiated a resolution that required IBM to market CP/M-86 alongside PC DOS. However the list price differential, $40 vs. $240 for the DRI product, discouraged consumer interest in the latter. Davis says “IBM clearly betrayed the impression they gave Gary and me.” [2]

DRI continued to thrive for several years. CP/M-86 paved the way for a host of new products. CP/Net allowed cheap, simple microcomputers with no local disk storage to operate as clients from a central multiprogramming server. Concurrent CP/M-86 offered a multi-tasking operating system for the IBM PC-XT. Kildall acquired Gordon Eubanks’ Compiler Systems Inc. for CBASIC and appointed him to head a language division. Both of these programs continue in daily use worldwide embedded in OS 4690, IBM’s operating system for point-of-sale terminals. The company also introduced operating systems with windowing capability and menu-driven user interfaces years before Apple and Microsoft.

In other pursuits, Kildall founded KnowledgeSet with Tom Rolander where they created the first CD-ROM encyclopedia for Grolier. Brian Halla, Intel’s technical liaison to DRI, recalls that he “showed me this VAX 11/780 that he had running in his basement and he was so proud of it and he said, ‘I figured out a way to have a computer generate animation,’ and he said, ‘Watch this. And he runs a demo of a Coke bottle that starts real slowly and starts spinning and so as maybe several months went by, he lost interest in this and he sold his setup to a little company called Pixar.’” [9]

At its peak DRI employed over 500 people and opened operations in Asia and Europe. However by the mid-1980s, in the struggle with the juggernaut created by the combined efforts of IBM and Microsoft, DRI had lost the basis of its operating systems business. Gordon Eubanks recalls that “It became clear to me that Digital Research did not have the will to win and they were losing opportunities. So I went off and did my own thing.” [10]

Dispirited, Kildall, who never enjoyed the responsibility of managing a large company or displayed the business acumen of Gates, and the other investors sold the company to Novell Inc. of Provo Utah in 1991. Ultimately Novell closed the California operation and in 1996 disposed of the assets to Caldera, Inc., which used DRI intellectual property assets to prevail in a lawsuit against Microsoft. [11]

After leaving DRI, Kildall continued to innovate. He moved to Austin, Texas where he founded Prometheus Light and Sound to explore wireless home networking technology and participated in charitable work for pediatric AIDS.

Gary Kildall died at age 52 following an accident in Monterey in 1994. His ashes were buried in Seattle, the hometown that he shared with Bill Gates.

In 1995, the Software and Information Industry Association presented a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award to Gary Kildall citing eight significant areas in which he contributed to the microcomputer industry.

Despite these widely recognized technical accomplishments, his legacy remains mired in a tangle of myths and conspiracy theories. The most persistent being driven by a 1982 comment attributed to Bill Gates and published in the London Times newspaper that “Gary was out flying when IBM came to visit and that’s why they did not get the contract.” [2]

The former editor of the Times, Harold Evans atoned for that story in a PBS documentary and his book They Made America: Two Centuries of Innovators from the Steam Engine to the Search Engine. The subtitle of the chapter on Kildall, “He saw the future and made it work. He was the true founder of the personal computer revolution and the father of PC software,” offers a sympathetic telling of the life and times of the brilliant and flawed genius who helped give birth to the PC operating system 40 years ago this year.

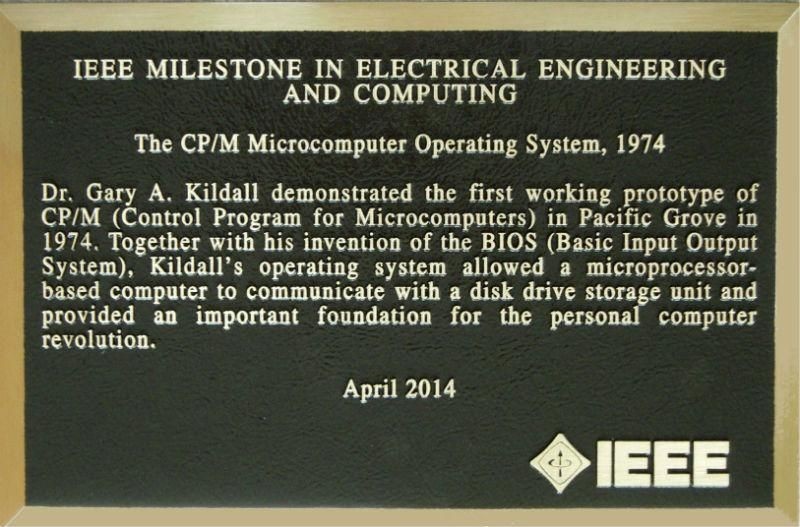

IEEE Milestone plaque installed outside 801 Lighthouse Avenue, Pacific Grove, CA

On April 25, 2014, the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering “The world’s largest professional association for the advancement of technology” will install a bronze IEEE Milestone in Electrical Engineering and Computing plaque outside the former DRI headquarters at 801 Lighthouse Avenue, Pacific Grove, CA. The Milestone program honors important events in electrical engineering and computing. Achievements such Thomas Edison’s electric light bulb, Marconi’s wireless communications, and Bell Labs first transistor are recognized with a plaque in an appropriate location. The citation reads:

I would like to thank all those who have contributed information and background to this article, especially to Tom Rolander, John Wharton, and Herb Johnson who maintains a wealth of information on CP/M and the history of DRI on his website at: www.retrotechnology.com/dri/index.html

For more information about the IEEE plaque commemoration see: “Legacy of Gary Kildall - Event April 25, 2014” at www.facebook.com/KildallLegacy.