Scattered on floppy disks and hard drives around the world, there may be millions of works of art created on now-archaic computer systems. Most of these are personal treasures, perhaps of value only to their creators or to their immediate circle of friends and family. Some computer art is of interest to researchers as an example of the progression of artistic tools that were used at a given time. Still others are just bad art, best forgotten.

What happens when a major figure in the art world has created works on a system that is decades-old and whose images are stored on potentially unreadable media? That was exactly the problem that faced a team of student researchers, curators, and perhaps most significantly, artist Cory Arcangel, in relation to the files created by the legendary Pop Artist Andy Warhol on the Amiga.

One of the forty-one disks disks containing Andy Warhol’s Amiga files

Cory Arcangel describes himself as an ‘Acolyte of Andy Warhol.’ “Between DuChamp and Warhol, those are the two big influences for the kind of art I make,” says Arcangel. Arcangel’s works span both physical and digital realms, as well as static and moving pieces, much like Warhol’s own works. Videos such as A couple of thousand short films about Glenn Gould and Sans Simon, as well as web-based works like Punk Rock 101, and even Nintendo cartridge hacks like Super Mario Clouds, make arcangel a multi-dimensional artist whose works can be seen as inhabiting areas that Warhol himself likely would have waded into had he not died in 1987.

Arcangel noted Warhol’s influence, “…when I first moved to New York and started becoming an artist, you know, I read his diaries, and for me, they were really helpful because they taught me, in a way, how to be an artist. Not in the poetic sense, but in the day-to-day sense, like ‘I went to work today. I made three paintings. Then I went to an opening.’ like a real kind of ‘this is what you do if you’re an artist. The life of an artist’”

Warhol’s interaction with the Amiga started with the introduction of the Amiga 1000 computer in 1985. He took part in a launch event at New York’s Lincoln Center, creating a piece of very Warholian art, using a scanned image of Debbie Harry of the New Wave act Blondie. “I’m going to do this ‘How to Paint’ thing that this computer company wants me to do,” Warhol noted in his diaries. It was a video of the event uploaded to YouTube, along with the mention in the Warhol diaries, that caught the attention of arcangel, who has used obsolete technology in many of his works. He became interested in Warhol’s work with the Amiga, in particular, whether any of Warhol’s floppy disks had survived. He contacted the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh in a quest to find out more about the condition of Warhol’s Amiga works and equipment.

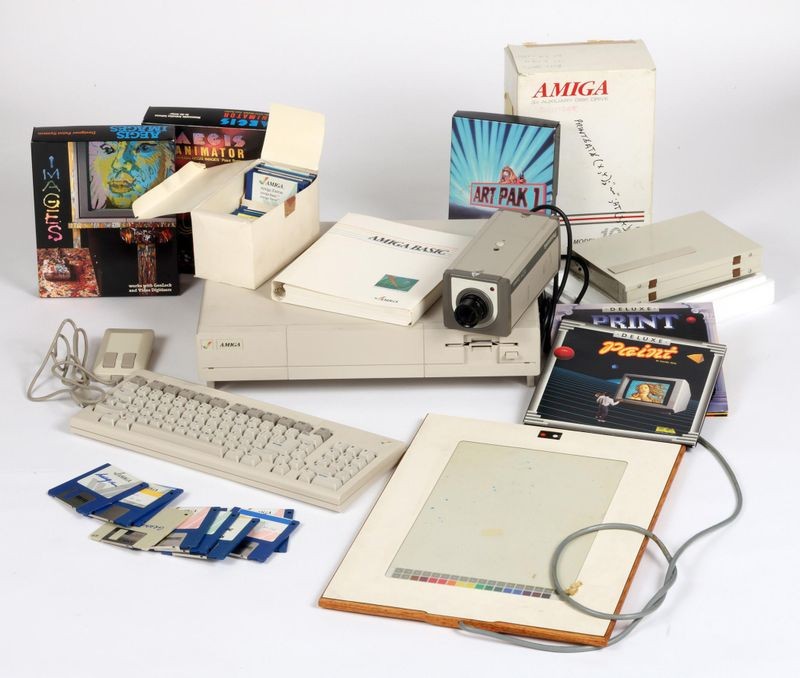

Commodore Amiga computer equipment used by Andy Warhol 1985-86

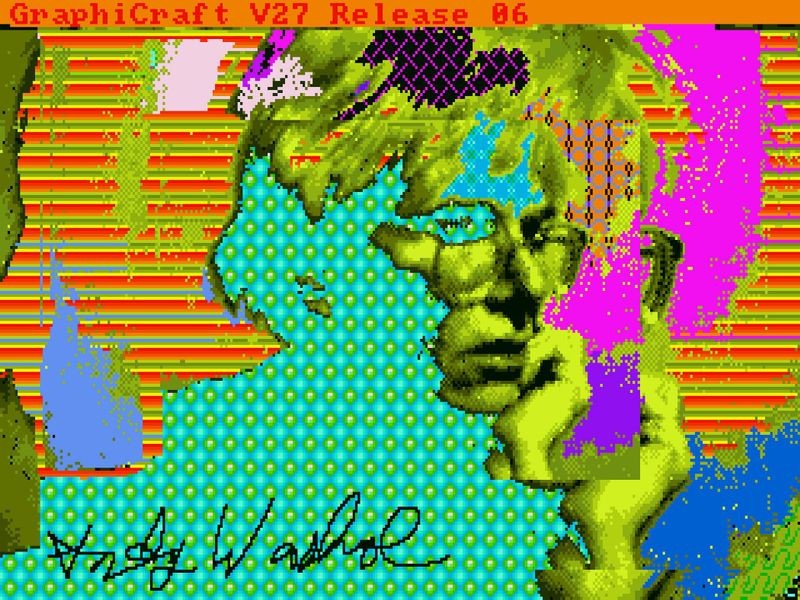

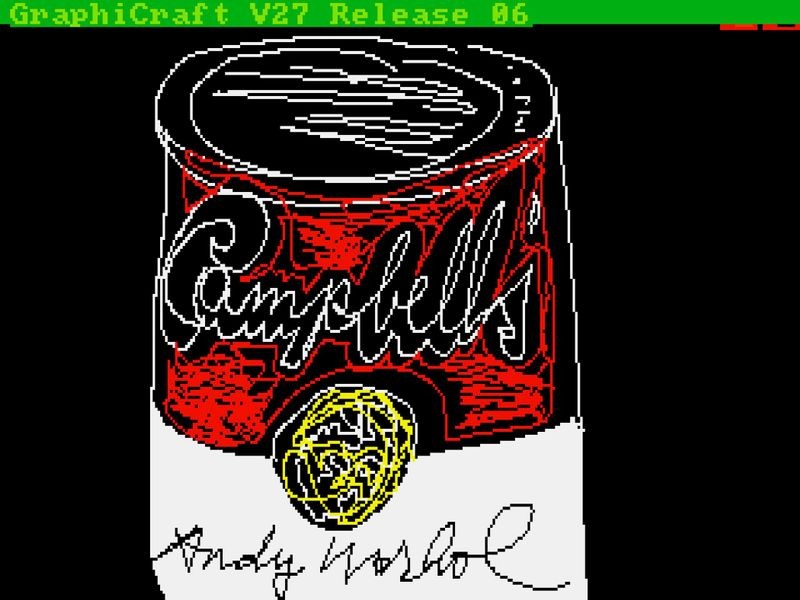

Warhol was given at least one full Amiga 1000 system with a drawing pad, camera, and various pieces of drawing software. He created several works on the Amiga, often using familiar subjects such as Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s soup cans, but giving them a new sensibility harnessing the techniques that the Amiga provided. Using the GraphiCraft painting system and other software, for example, Warhol created images that emulated techniques similar to his silkscreen creations of the 1960s, such as bright colors layered over black and white photos of celebrities and newspaper photos.

After his death, Warhol’s works, as well as a great deal of other material, eventually went to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Commenting on this massive amount of material, Arcangel told Themed for Your Pleasure podcast host Vanessa Applegate, “Warhol was a hoarder. A maximum, a hundred and twenty percent hoarder, so the amount of material that the Warhol Museum has is mind-boggling.” This led to much of the material being little examined; not lost, but over-looked among hundreds and thousands of other items relating to Warhol’s life and art.

“The (Warhol) museum has so much stuff, they’re still going through it.” Arcangel noted. Among the items were 41 floppy disks, Warhol used to store the works he created on the Amiga. These disks contained many pieces, and while Museum archivist Matt Wrbican knew of their existence, no attempt had been made to read the disks or recover the images.

Wrbican noted, “Really, we didn’t have any clue what was on the disks. At that point, I only knew of two images that Warhol had made (on the Amiga). I assumed there were lots of other images because Andy’s assistant Jay (Shriver) told me that he had played around with the images for a while, but exactly what those images were I had no idea.”

The two images Wrbican had seen, the Debby Harry photo manipulation done at the Amiga Launch and a self-portrait created for the cover of Amiga World Magazine, were widely-known, but no one was certain about the contents of the disks the museum held.”They were as well taken-care of as they could be. They were in incredible shape,” arcangel noted.

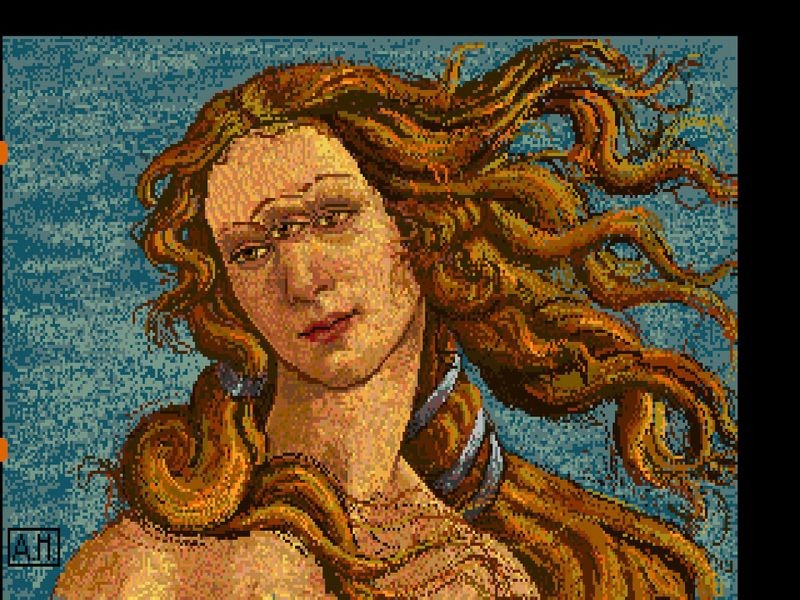

Andy Warhol, Venus, 1985, ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

In 2011, Arcangel connected with the Carnegie Mellon University Computer Club, known for a great many retro-technology feats. Working with Arcangel, Wrbican and others, members of the club began reading the disks, using the best digital archival practices. The Kryoflux, an interface that allowed them to read disks from the Amiga and bring the files into a modern PC, way key. One rule was that each disk should only be handled and read only once. “They were like ‘we need to do it with the Kryoflux. We need to do it at the lowest level. They were the people pushing, making sure everything was at a very high level, [an] archival preservation project. I can’t say enough nice things about the Carnegie Computer Club,” arcangel said, “there is nothing cooler than a retro-computing hacking club in my mind! Especially at a place like Carnegie Mellon.”

By the end of 2013, the club had read all of the disks and began working on recovering the individual files using emulators running on modern PCs. The recovered images were definitely Warhol creations, and while rather small by today’s standards (200 x 300 pixels), they show Warhol’s famous style. Using techniques and tools like the paint bucket and fill, he created images that felt like the silkscreened photograph-based works that have become beloved and highly collectable in the years since. A self-portrait, called Andy 2, features a photo of Warhol that has had fields of textured color layered over it. The effect is right in line with his self-portraits of the 1960s and 70s. “…They were really amazing,” arcangel says. “There’s one of Marilyn Monroe that he had sort of splashed all over… Fantastic!” and “he couldn’t have done any better.”

Andy Warhol, Andy 2, 1985, ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Not all of the pieces recovered were intended to be artworks. Some were test pieces used to discover the capabilities of the Amiga. In much the same way a painter may hone brush technique through practice on works never intended to see the light of day, Warhol apparently created similar images to allow himself to experiment with the Amiga environment.

arcangel commented, “what is amazing to me is that he seemed to get it really quick, really quick… how to work with the computer, and how to work with the paint bucket. You can see a couple of them where he’s trying to learn the copy/paste [function] and he’s learning to use the paint bucket, and then all of a sudden, there are a couple that are just amazing.”

He also created images from scratch, including a Campbell’s soup can–the iconic image of his days as Pop Art’s leading practitioner and art world Bad Boy. The mainstream art establishment had been slowly embracing works done with the aid of computers since the 1960s, but these works were created with large computers—including mainframes and supercomputers. Steve Jobs had made it something of a mission to bring the Macintosh to artists. The artist Keith Haring had been introduced to the Apple Macintosh computer at the same time as Warhol, but integrated it into his work much more. Graphic artists had also gravitated towards the Mac, but the Amiga was billed as a ‘Multi-Media Computer,” and that may have drawn Warhol towards it.“The thing that I like most about doing art on the computer is that it looks like my work.” Warhol once said.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s, 1985, ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Arcangel’s passion for the project, the skill and technological know-how of the CMU Computer Club, and the background of the archivists and curators at the Andy Warhol Museum, all led to the extraction of twenty images. The disks, along with Andy’s Amiga 1000 computer, his software, graphics tablet, camera–as well as the images that the Carnegie Mellon Computer Club extracted from the disks–are in the permanent collection of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. A documentary, The Invisible Photograph: Part II (Trapped), chronicles the interactions between the Warhol Museum, the CMU Computer Club, and Arcangel, as well as the Warhol-Harry portion of the Amiga product launch. These materials show how one of the most significant artists of the 20th century expressed his artistic vision using one of the most important tools ever created, the computer. They also represent some of Warhol’s final art pieces, created over the last eighteen months of his life.