By 1987, the PC revolution was well entrenched and underway. Desktop PCs were standard hardware for home enthusiasts, businesses, government agencies, and computer labs tucked away in college campuses. Apple was busy rolling out new versions in their Macintosh line of computers and was also introducing a new generation of schoolchildren to Apple computer products by offering steep discounts on their equipment to school districts across the country. However, some prognosticators were also fast at work forecasting the future of a new generation of computing devices – and traditional PCs were not what they had in mind.

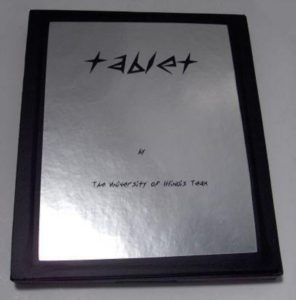

Tablet: PC of the Year 2000 prototype from the University of Illinois (CHM# X876.88)

The PC of the Year 2000 competition was an Apple-sponsored challenge initiated in 1987 that aimed for designers to predict and create a prototype of exactly what its name suggested. The winning team from that contest, a competition that included 1,000 university students in teams that were consisted of up to five members, was a group from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). The judging panel of Ray Bradbury, Alan Kay, Diane Ravitch, Alvin Toffler, and Steve Wozniak selected the winner, which was aptly named “Tablet: Personal Computer of the Year 2000.” The prototype was later donated to the Museum, and is now part of CHM’s permanent artifact collection.

Tablet devices were not an entirely new concept, and their lineage goes back at least as far as 1963 with the RAND tablet, which was in part designed to develop progressively sophisticated modes of human-computer interaction by means of graphical languages. While its capabilities bear very little resemblance to what was envisioned by the UIUC team, its input mechanism was a flat writing surface, and underneath was a grid of wires capable of transmitting handwriting and freehand drawings from a stylus to an attached display.

The RAND Tablet input device (CHM# X450.84) ©Mark Richards

Furthermore, Alan Kay’s Dynabook concept from 1972 inspired a numbers of designers with many of its speculative innovations. Tablet-like devices also appeared in a number of 1960s science-fiction television shows and movies, including several examples from Gene Rodenberry’s classic Star Trek series. The tablets featured in these productions bear a much closer resemblance to the Tablet conceived of in the PC of the Year 2000 contest, but predicting the future is not an exact science. According to Kay, “the best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

Although a 2000-era everyday PC is not described in the UIUC paper, a survey of the 20-plus page report submitted to the judging panel revealed a number of prescient statements and descriptions reminiscent of today’s tablet computers and their applications. So what exactly did this particular project – envisioned by a group of students with faculty advisors – get right? Well, if one fast-forwards 10 years from the winning submission’s nominal year 2000 to 2010, quite a bit actually.

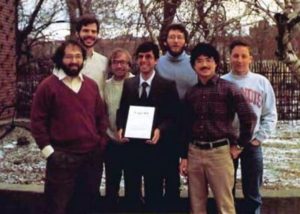

UIUC’s winning team (from left): Stephen Wolfram, Stephen Omohundro, Arch Robison, Steven Skiena, Bartlett Mel, Luke Young, and Kurt Thearling. Source: University of Illinois

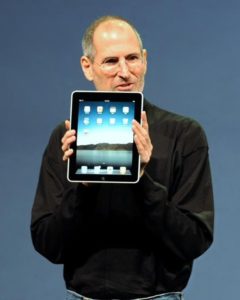

Today’s tablet consumers could easily read the team’s physical description of their Tablet as a description of an original iPad released in 2010: “This rectangular slab will…have no buttons or knobs to play with…On powering up our machine, icons representing…a host of applications will appear.” Further statements describe a touchscreen display as its input mechanism, and in its entirety, their concept mirrors one of Apple’s design philosophies of simplified elegance. The Tablet’s dimensions were based on the familiar size of a standard paper notebook, and the team notes that, “No one thinks twice about bringing a pad into a meeting, the library, or the toilet.” Add an “i” to “pad”, and this sentiment would certainly resonate today.

Furthermore, the team anticipated several particularly on-target applications for tablet computers, and computers in general. In what sounds like a pitch to early Facebook investors, the team predicted a killer app that is today a hugely popular function of all computing devices – social media broadcasting and consumption. “Each machine can continually broadcast what the owner wishes the world to know about him or her: perhaps their name, face, interests, and marital status for openers. Setting your machine in ‘get acquainted mode’ will display the location of all machines in the vicinity and who their owners are. Just imagine turning this loose in a singles bar!” The first sentence could fill in as a concise description of Facebook, and the statement as a whole illustrates functions that closely resemble contemporary proximity-based dating apps like Tinder or Grindr.

In another foretelling statement, “Using CCD cameras, home movies take on a new meaning… As the technical and financial obstacles to entry for such arts fall, more and more people will participate… Some form of ‘shareware video’ might arise. Other distribution channels will no doubt sprout up.” In this statement, the team hinted at an application that in many ways resembles YouTube. While public broadcast of funny home videos was once relegated to network TV shows and specials, viral videos consumed on YouTube are today some of the most shared files over the Internet, and a large portion are created, consumed, and shared with tablets.

A few more predictions evoke an air of similarity with today’s handheld computing environment: “The threat of theft will be eliminated… We can call up the computer… and use the GPS receiver to let us know exactly where it is.” Apps like Find My iPhone are a clear descendant of such an idea, and although theft of mobile devices has not been fully deterred, the headache of losing a device has been greatly diminished. With pinpoint accuracy, GPS can track the exact location of devices when the feature is enabled. Also highlighted by the Tablet team is another, and currently widely used, GPS application – navigation. “Taking our computer for a drive, it can provide us with an ideal route between two points by considering the possible routes, the time of day, and current traffic patterns.” GPS directed driving routes and the familiar humanoid voices of our computer “navigators” have now become commonplace.

Steve Jobs showing off Apple’s iPad

In addition, with high-resolution video and cellular phone link capabilities, mobile video conferencing was recognized as a possible feature for the Tablet. Clearly, contemporary tablets are communication devices, and video calls are a common mode of communication. Apple’s FaceTime was introduced alongside the iPhone 4 in 2010 and became available for the iPad’s second version in 2011. The high-resolution video aspect of the Tablet was also touted as a platform upon which the entertainment possibilities of the device can be built. Today, cable providers have developed apps that allow users to watch TV on tablets, a feature forecasted in the report. Unmistakably, two of the primary usages of today’s tablets are communications and entertainment – both described by the Tablet team.

While the winning submission to Apple’s competition hints at many similarities to contemporary tablets, some of the predictions did not ring true with today’s reality. For example, the Tablet team described a pen-like stylus as its primary input medium. Although styli and handwriting recognition software did gain a foothold with numerous mobile products in the 1990s, fingers, which the UIUC team called “low-resolution devices,” are currently the most common way for interfacing with tablets for everyday applications. Steve Jobs called the finger “the best pointing device in the world.”

Inner workings of the UIUC Tablet prototype including the LaserCard Mass Storage Unit (L)

Another off-the-mark prediction was use of removable storage media the team called LaserCards. The team stressed that this replacement over past storage solutions like hard disk drives would improve the physical integrity of the device. While some handheld devices, like the first versions of the iPod, used hard disk drives, the inherent relatively rough handling of mobile devices makes those types of drives more prone to failure. So in this aspect, the Tablet designers correctly envisioned a transition to a more stable platform.

Interestingly, just around the same time that UIUC team was busy prognosticating the future of PCs, another team – backed by the resources of Apple Computer itself– was hard at work conceptualizing a similar product. A video released in 1987 by Apple showcased the “Knowledge Navigator.” It was a fold-out, tablet-like device first envisioned by Apple CEO John Sculley in his autobiography Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple. If the functionalities shown and described from the Knowledge Navigator and the winning submission from the PC of the Year 2000 contest were melded and shaped together, that new device would in many ways become an even clearer vision of Apple’s current iteration of tablet.

In the promotional video for the Knowledge Navigator, a video conference akin to a FaceTime chat is showcased, a Siri-like program serves as a principal means of interfacing with the device, finger swipes are used on the touchscreen to make selections, and colleagues share files over a network. Nearly all of the capabilities described by both the UIUC and Knowledge Navigator teams existed when they were first proposed, but these ideas and visions, and those of others as well, were dispersed and not consolidated into a singular vision.

Knowledge Navigator promotional video, 1987

Although the release of the iPad in 2010 brought the tablet computer to a huge user base, there are a number of earlier touchscreen tablets or tablet-like devices – including the EO Personal Communicator 440, Newton MessagePad, Aqcess Qbe, Cyrix WebPAD, and the Windows XP Tablet – that failed to gain a firm foothold amongst consumers. These devices are only a few of the tablets developed since 1987, and all of those products, including unproduced concept designs, collectively contributed to what consumers use today. A quote attributed to futurist William Gibson encapsulates a theme found in many innovative technologies: “The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” This harkens the question, what will the PC of the year 2030 look like? Assuredly, it is likely here right now, its attributes unevenly distributed across the vast array of tech gadgets and products that are becoming more ever-present in everyday life.