In July of 2017, I embarked on what has become something of a professional obsession: documenting the impact of computing—from vacuum tubes to social media—on the world of music. I began putting together a pitch-packet of names to interview. The list included researchers like David Cope and Gareth Loy, synthesizer developers such as the sadly departed Don Buchla, composers like Suzanne Ciani and Laurie Anderson, and performers such as Mark Goldstein. I had a single name at the top of the list that I knew would start us off on the right foot.

The name was Mark Mothersbaugh.

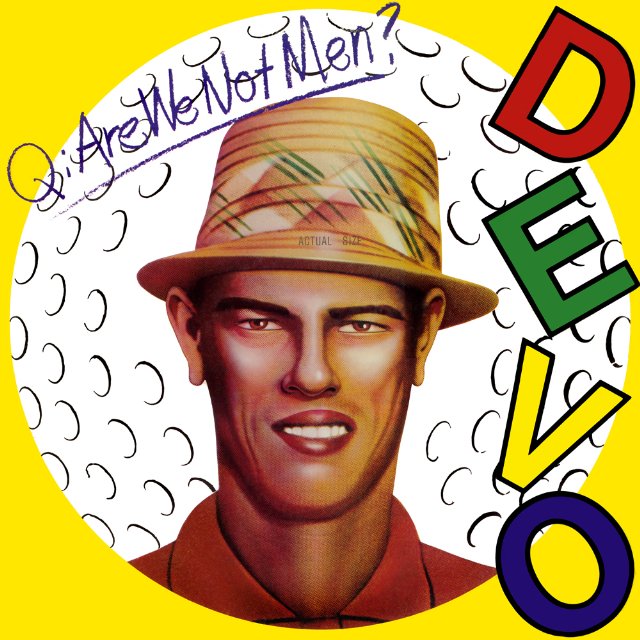

The cover for DEVO’s studio album debut—Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are DEVO!

If you’re familiar with popular music of the 1970s and 1980s, you’ve probably heard of DEVO. They burst onto the scene in the 1970s with an ambitious combination of punk rock sensibility and science-fiction aesthetic. They were technically complex with an inventive musicality and exuded an early post-modernist philosophical outlook that permeated everything. As the lead singer of DEVO, Mothersbaugh provided much of the structure the band’s music was created around and ultimately helped define an influential sound that has spread from art rock to surf rock and just about everything in-between.

DEVO started in 1973 at Ohio’s Kent State University, where Mothersbaugh was an art student. The initial line-up featured Mothersbaugh singing as well as playing guitar and keyboards, Jerry Casale on the base, Bob Lewis on accompanying guitar, and Jim Mothersbaugh on drums. Key to the band identity was the events of May 4, 1970, when the Ohio National Guard opened fire on students protesting the Vietnam War. Casale witnessed the shootings and knew two of the victims. Following the attack, Casale and Lewis began to create satirical artworks based on the idea of de-evolution. Mothersbaugh, having met the pair earlier in 1970, became a collaborator, adopting the idea of de-evolution in his own art and music.

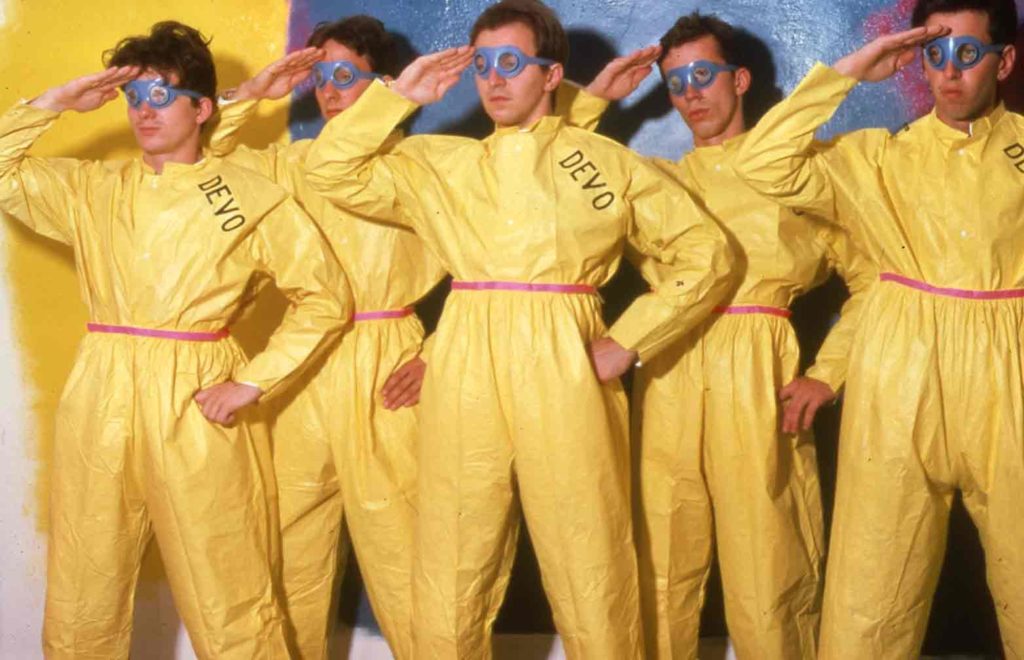

An early performance by DEVO at Kent State. Image Credit

This concept permeated everything the band did, from live performances to recordings. The group interpreted the idea of de-evolution by blending post-Structuralist art philosophy and science-fiction tropes with music that combined influences from rock ’n roll and art music.

Mark Mothersbaugh performing as Booji Boy. Image Credit

The band played incredibly theatrical live shows that might include Mark donning a mask, climbing in a baby’s crib and performing as the character Booji Boy. They toured widely, releasing not only records, but well-received art films such as The Truth About De-Evolution. It was through those films that the band came to the attention of David Bowie, who got them signed to Warner Bros. Records. This, and a performance on Saturday Night Live on October 18, 1978, soared DEVO to new heights.

From the beginning, DEVO used electronics within their music, including a homemade set of electronic drums. As the band’s reputation, and income, increased, they added more and more electronic elements.

One instrument that DEVO used widely in their music was the Minimoog synthesizer. A keyboard-based synthesizer that defined much of the band’s sound in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Mothersbaugh also began to work with more complicated commercial computer-music devices.

Mark Mothersbaugh’s Fairlight CMI II

The Australian Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument, or CMI, was one of the earliest digital music workstations, combining a digital sampling synthesizer, a standard piano-style keyboard, and computer system complete with keyboard, visual display, and light pen. The system could capture sounds, which could be modified using various software packages. The ability to modify music, especially with a light pen, and be able to play it back automatically through the instrument revolutionized the way many musicians interacted with their compositions.

DEVO was far from the only pop music act diving into the Fairlight system. Peter Gabriel, Jan Hammer, Duran Duran, and, perhaps most notably, Jazz legend Herbie Hancock. The Fairlight was one of several musical workstations to appear in the 1980s, helping to redefine pop music’s sound through the application of new technologies. The system changed the way many composers and musicians worked, and for Mothersbaugh, it gave him a new view on the individual tones and sounds with which he worked.

DEVO promotional photo

The 1980s saw DEVO achieve chart success with their song “Whip It,” which was the only DEVO song to appear in the Top 40 singles chart. Following the commercial and critical disappointment of their 6th album Shout, which some criticized for over-reliance on the sampling done with the Fairlight, DEVO was dropped from the Warner Bros. Record label.

It was also during this period that Mothersbaugh began to compose for television and film projects, beginning with Paul Reubens, a.k.a. Pee-Wee Herman, who asked Mothersbaugh to write music for the television program Pee-Wee’s Playhouse.

Mark Mothersbaugh and his production company Mutato Musika have created dozens of soundtracks, including The Lego Movie in 2015.

With this new freedom, Mark began creating music for many different programs, later expanding into film and video games over time. In 1989, Mothersbaugh founded Mutato Muzika, a music production company for television, film, and commercials.

Mothersbaugh was never far away from his roots as a visual artist. He worked in screen printing, photography, painting, and drawing throughout his time in DEVO, even creating covers for DEVO’s albums. In the 1990s, Mothersbaugh discovered Photoshop.

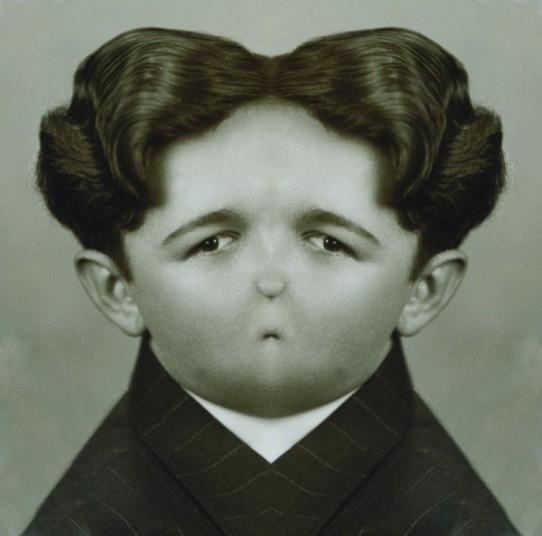

One of Mothersbaugh’s long-time art practices was creating mirror-image photos, investigating the myth that human faces and bodies featured a perfect symmetry. He was never fully satisfied with his original process, which used a mirror and camera, always leaving a tell-tale black line where the mirror would sit.

A Beautiful Mutant by Mark Mothersbaugh. © Mark Mothersbaugh

Later, using antique photographs, mostly studio portraits, Mothersbaugh began experimenting with a computer to manipulate the images.

He’s collected these images into a book, Beautiful Mutants, featuring hundreds of Photoshopped images. The results range from playful, with subjects taking on mutations such as three or arms or a single eye, to uncanny, as in the case of young man wearing a horned devil’s mask.

DEVO has reunited a few times, but Mothersbaugh has kept working on his solo projects, including scoring films by Wes Anderson, like The Royal Tenenbaums and Moonrise Kingdom, as well as major blockbusters like The Lego Movie and Thor: Ragnorak. Even now, when he might compose a half-dozen scores in a year while still occasionally touring with DEVO, he is also creating unique art works, like his orchestrions, on exhibit in the CHM Learning Lab.

Created from a combination of bird whistles, duck calls, and pipes from decommissioned church organs, Mothersbaugh’s orchestrions are works of sound art that combine aspects of performance with sculpture.

The massive pieces, some more than seven feet tall, whistle music that is decidedly Mothersbaugh, calling to mind everything from circus organ music to cartoon scores.

Mothersbaugh’s orchestrions are controlled using MIDI, a standard interface that connects all electronic musical devices—like synthesizers, samplers, even computers—and allows them to communicate with each other.

Mothersbaugh programming orchestrions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, in 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mothersbaugh remains a leading figure in American popular music, still creating art, both audio and visual, always incorporating technology into his creative process. He was a natural place to start my investigation into the world of computers and music.

Oral History of Mark Mothersbaugh, interviewed by Christopher J Garcia on November 13, 2017 for the Computer History Museum. Transcript.

Discover Mark Mothersbaugh’s orchestrions on exhibit in CHM’s new Learning Lab.

An orchestrion (awr-kes-tree-uh n) is a mechanical musical instrument that may resemble an organ but sounds like a full orchestra. These imaginative instruments were popular among German nobility in the 1850s. But for contemporary artist and musician Mark Mothersbaugh (b. 1950), they capture his personal journey with technology and art.

Inquire with our front desk about demonstration times.