The Victorian “Internet”

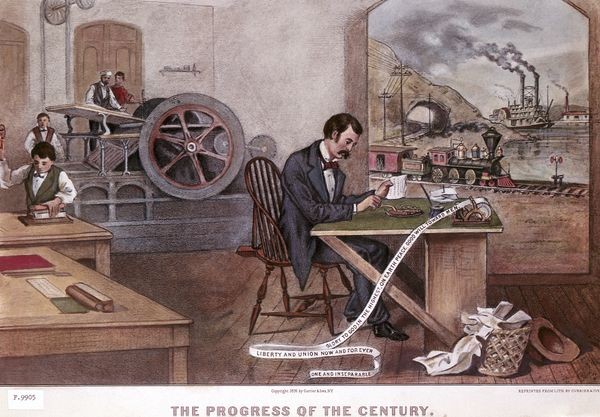

Telegraph operator

Telegraph offices were a familiar sight, especially in railroad towns. In the 1870s, a telegram cost around 50 cents -- about $20 today. Skilled Morse code operators were in great demand.

The Victorian “Internet”

Your great-great-Grandma wasn’t surfing the Web. But she may have been sending digital messages.

From ancient Greece until the 19th century, the semaphore was the fastest way to send messages. People used flags or lights to signal between line-of-sight stations. But in the 1830s, the telegraph pioneered a new concept: carrying information with electricity. That “big idea” became a building block of computers and telecommunications.

Telegraph networks rapidly circled the globe, joined later by telephones. Their providers evolved into some of the first major technology companies—many of which remain dominant players in telecommunications.

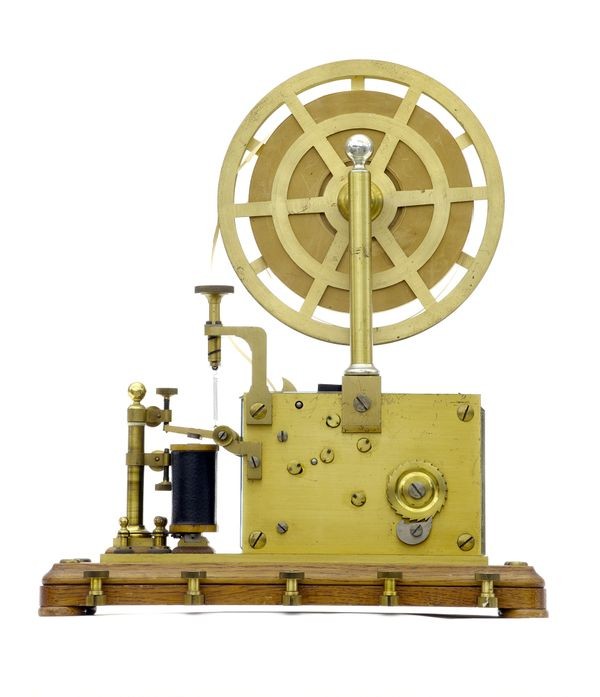

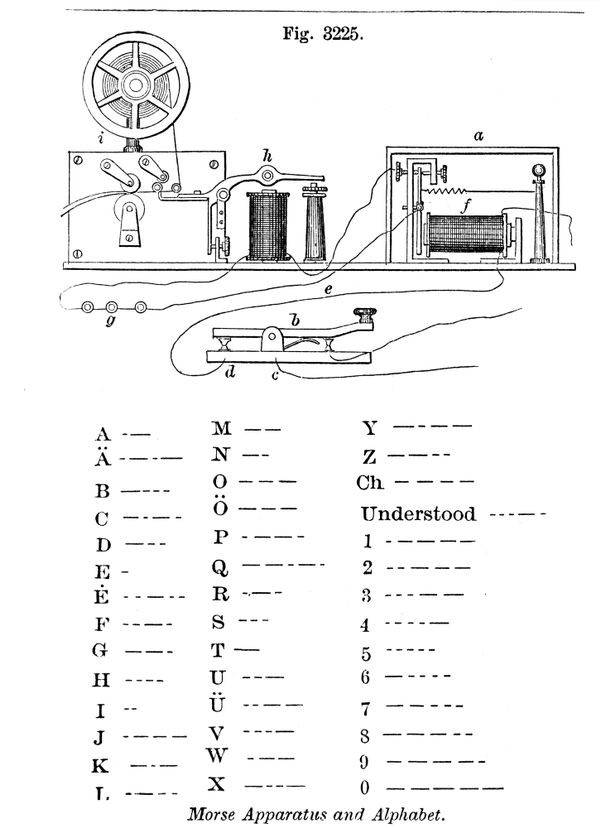

Telegraph sender key and receiver/sounder

Pressing the key at one end of the wire caused an electromagnet at the far end to energize and click the sounder. The wooden box amplified the sound. Experienced operators could send 20 words a minute.

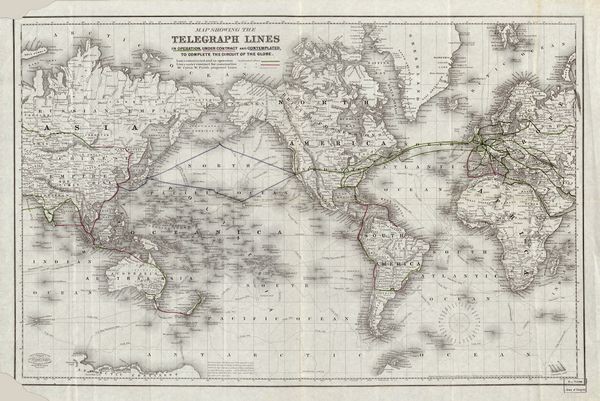

View Artifact DetailWorld telegraph map

With the 1866 transatlantic cable, the world’s continents were permanently connected. In many countries telegraph lines ran alongside railroads, which had flourished in the 1850s.

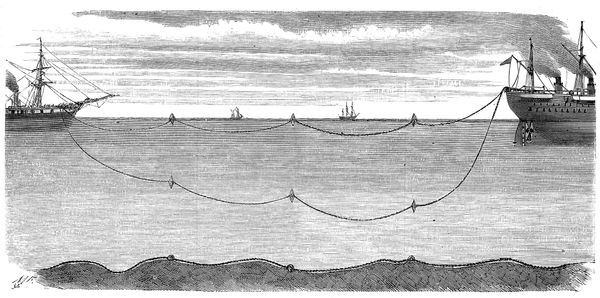

View Artifact DetailSection of first Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable

This cable, with 7 copper wires covered with natural rubber from trees, was wound with hemp and then wrapped by 18 protective stranded cables. It weighed only 6 ounces per foot but could withstand a pull of several tons.

View Artifact DetailUniversal 3-A stock ticker

Named for the ticking sound they made, ticker tape machines printed stock prices in real time as they were sent over telegraph wires from the stock exchange floor. The “Universal,” designed by Thomas Edison, printed in the range of 150-285 characters per minute.

View Artifact DetailL.M. Ericsson printing telegraph

This telegraph receiver recorded dots and dashes as indentations on paper tape, which a trained operator could read later.

View Artifact DetailLaying underwater cable

Laying cable without breaking it was difficult. Although it took several tries, by 1866 the transatlantic cable let Europe and the Americas exchange information at the speed of light.

View Artifact DetailTelephone receiver

Independently invented several times in the mid 19th century, the first telephones--and the telephone service--were expensive. They were initially used more by businesses than in the home.

View Artifact DetailWheatstone automatic transmitter

Englishman Charles Wheatstone, who had also invented a telegraph, developed automatic transmitters for sending messages punched on paper tape at high speeds. These were often used on underseas cables.

View Artifact DetailGoing Digital: Morse Code

Morse code, the most common “language” of telegraph systems, represents information digitally.

Electrical switches made “dots” and “dashes”—like a computer’s ones and zeros. Receivers turned these pulses into sounds. Messages were sometimes stored on paper tape as embossed lines or, later, punched holes that could be read by machine.

Morse code chart

Redesigned by Samuel Morse’s assistant Alfred Vail around 1840, “Morse” code was more reliable than competing systems. It dominated telegraphy, and later, military and long distance radio communications, until the 1990s.

View Artifact Detail