IBM Catches Up

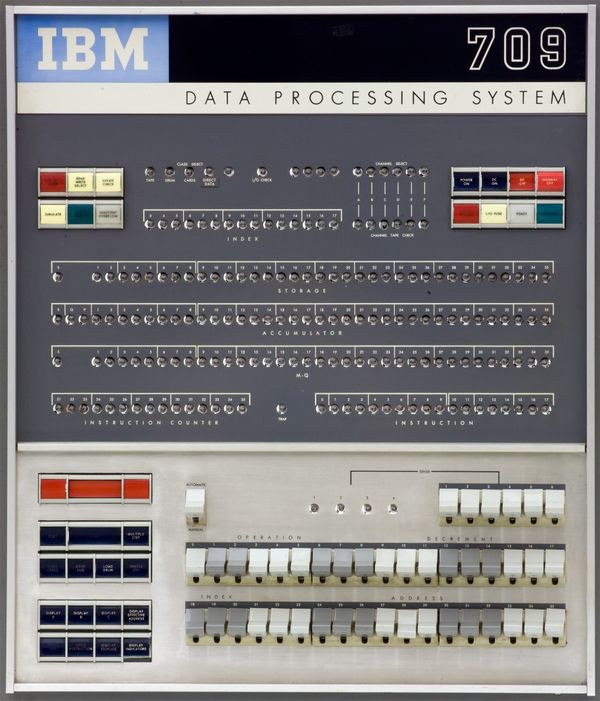

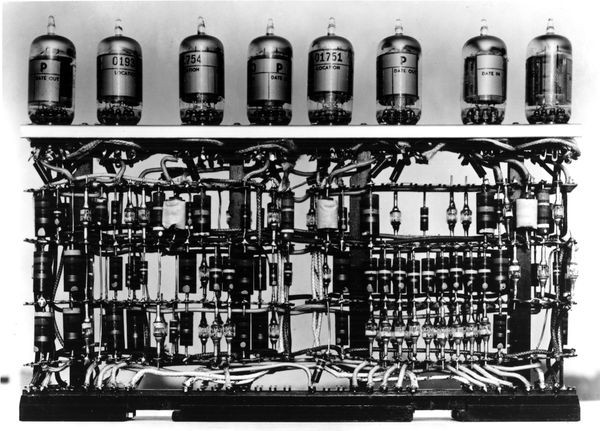

709 Data Processing System control panel

The IBM 709 was the last of IBM’s large, scientific, vacuum-tube computers. Ease of programming and high-speed input/output were distinctive features. IBM announced a transistor-based successor in late 1958.

IBM Catches Up

IBM got a jolt in 1951 when it lost the Census Bureau business to UNIVAC. That setback reenergized IBM, which had dominated pre-computer data processing.

Determined to meet the challenge—and eyeing data processing needs in the Korean War—IBM designed its 701 computer in just one year. After that, a flurry of new models eroded UNIVAC’s lead.

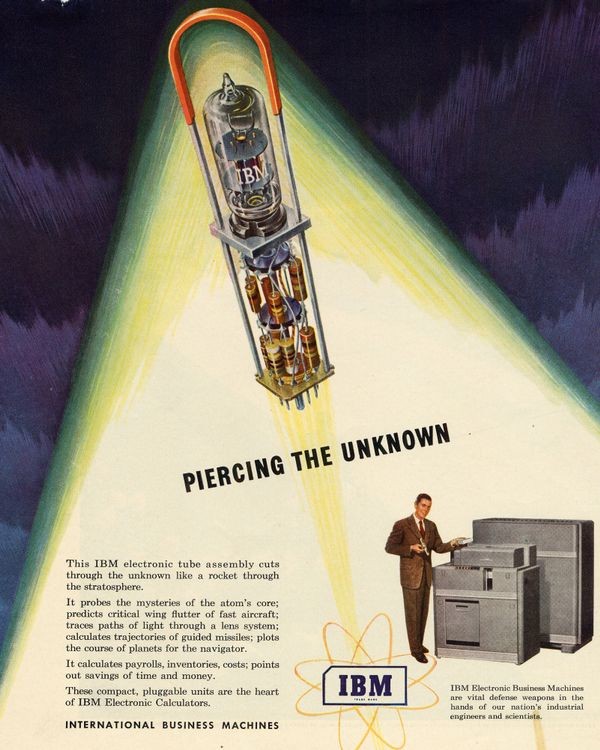

IBM "Piercing the Unknown" advertisement

IBM positioned itself as a technological leader in the new age of atomic energy and rockets.

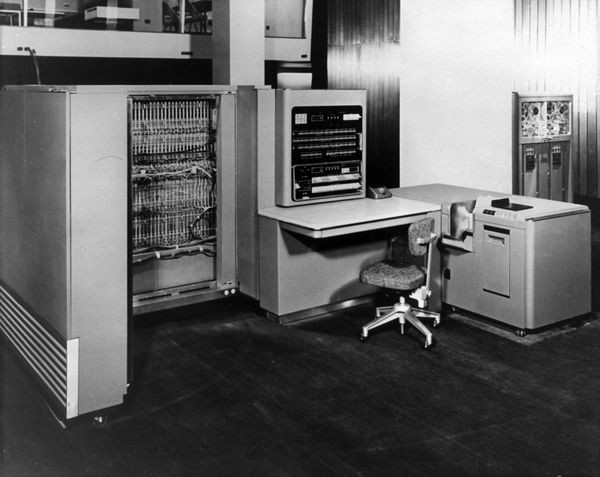

View Artifact DetailIBM Card Programmed Computer (CPC)

This “Electronic Calculating Punch” could execute up to 60 plugboard-controlled program steps. When customers hooked up an earlier version to accounting machines, IBM saw the benefit and offered a “Card Programmed Calculator” based on the 604.

View Artifact DetailIBM 650 System

IBM’s original forecast for the 650 predicted selling 50 machines. But at less than $4,000 per month to rent, it became a winner. Nearly 2,000 were produced. The machine’s logic used vacuum tubes, its main memory a magnetic drum.

View Artifact DetailIBM 701 Electronic Data Processing System

Thomas Watson Jr. called IBM’s first scientific computer, “the machine that carried us into the electronics business.” Its initial reliability was poor, in part because the 2K word memory was made from 72 Williams-Kilburn CRT tubes.

View Artifact DetailIBM 701 assembly floor

IBM did the final assembly, but more than 400 companies supplied parts and subassemblies for its computers, including GE for vacuum tubes and 3M for magnetic tapes.

View Artifact DetailIBM 709 Data Processing System

The 709 scientific computer was compatible with the earlier 704, and offered better input/output performance. It had a short life, however: a transistor-based version, the 7090, replaced it a year later.

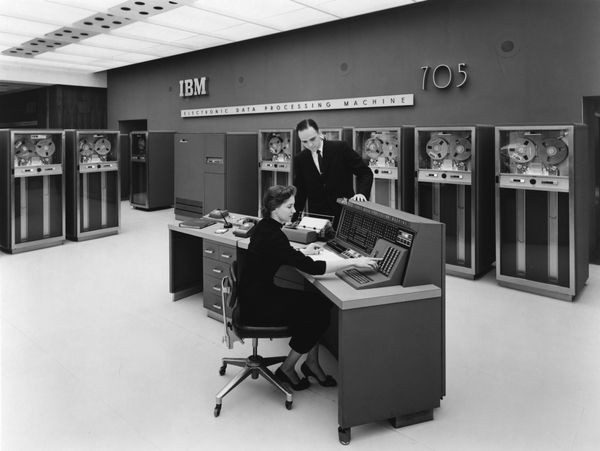

View Artifact DetailIBM 705 Data Processing Machine

Product cycles were brutally short in the computer industry, then as now. This commercial computer with fast core memory made its predecessor, the 702, obsolete after just one year.

View Artifact DetailThomas Watson, Jr. (1914-1993)

After college, Thomas Watson Jr. worked as an IBM salesman, but resented the special treatment he received as son of the company’s President. Becoming a pilot during World War II finally gave him confidence in his own abilities.

View Artifact DetailIBM 701 vacuum tube plug-in unit

The replaceable vacuum-tube modules introduced with the 604 multiplier allowed quick repairs when compared to a large wired chassis. The modules became the standard for all the 700-series computers.

View Artifact DetailType 706 Williams-Kilburn tube electrostatic memory prototype

Influenced by John von Neumann’s computer design at the Institute for Advanced Study, the IBM 701 used electrostatic memory. Each 706 storage unit had 72 cathode ray tubes, and each tube held 1,024 bits.

View Artifact DetailIBM 704 Electronic Data Processing System

With a $2M price tag and weighing over 30,000 lbs, the IBM 704 was not a casual purchase. But 123 customers decided that its advanced capabilities were worth the heavy investment.

View Artifact DetailIBM 702 Data Processing System

First called the Tape Processing Machine, the IBM 702 was aimed at commercial customers. They preferred that numbers be represented internally as decimal digits, not in binary as in scientific computers.

View Artifact DetailIBM 305 RAMAC

The “Random Access Method of Accounting and Control” (RAMAC) computer was used to maintain business records. It is best known for being the first computer with a hard disk, which replaced cumbersome files of punched cards.

View Artifact DetailWho Bought an IBM?

IBM’s evolving customer base reflected an evolving marketplace and postwar economic boom.

Its model 701 straddled the scientific-commercial line, with seven of the 19 produced sold to aircraft manufactures. IBM’s follow-on model, the 702, was designed more specifically for offices than engineers, bringing business applications to companies such as Bank of America and Ford.

Bank of America branch

Bank of America was an early adopter of the IBM 702 for its financial accounting, including inter-branch clearings. This branch stood on San Francisco’s Van Ness Avenue, a busy commercial area.

View Artifact DetailDouglas Aircraft assembly line

Aerospace firms were early customers of IBM’s first computer, the 701. Douglas Aircraft used it for engineering calculations, shaving months off its development of the DC-7.

View Artifact Detail