Robots before Computers

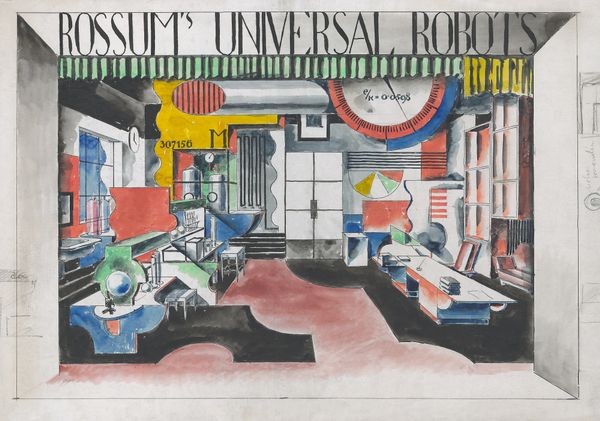

R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) stage design concept

The robot factory was more biotech than electronic, with “kneading troughs” for processing a chemical substitute for protoplasm.

Robots before Computers

Talking heads, flute players, digesting ducks, dancers, writing automatons—the industrial age brought a cavalcade of mechanical robots. Most were honest experiments with robotics. Some, like the chess-playing Turk with a person hidden inside, were fakes.

Robots in the 20th century supplemented the mechanics with electronics, creating movement that seemed more lifelike. Light detectors, touch sensors, and microphones provided input. Electric or hydraulic motors provided controlled motion.

But without computers to help them process the sensory data and plan actions, they were more brawn than brain.

Elektro and Sparko at the World’s Fair

Built by Westinghouse, the relay-based Elektro responded to the rhythm of voice commands and delivered wisecracks pre-recorded on 78 rpm records. It could move its head and arms…and smoke cigarettes.

View Artifact DetailWhy Are They Called “Robots”?

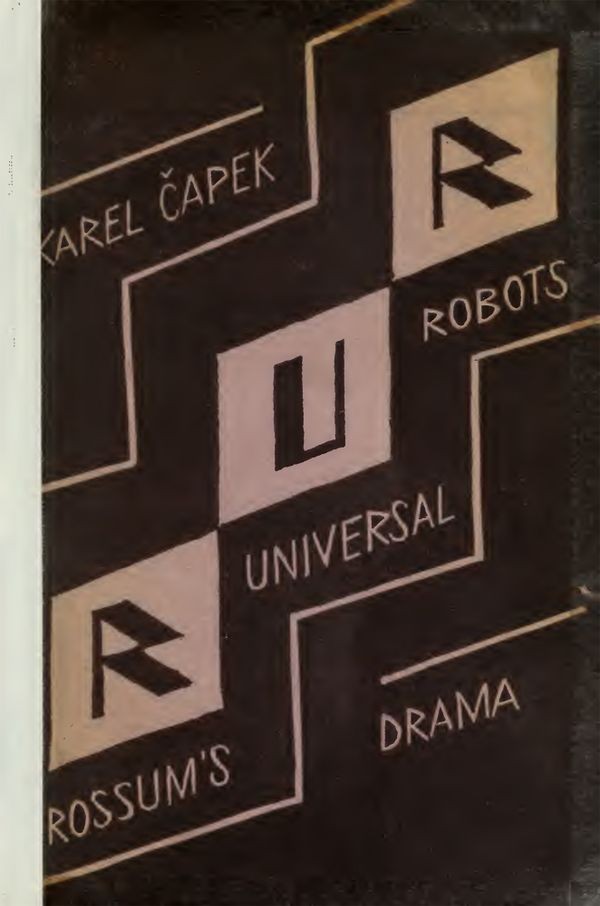

Playwright Karel Čapek introduced the term in his 1921 play, “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” from the Czech word robota, meaning slave labor. Čapek’s factory-built artificial people are at first helpful workers, but later rebel and destroy the human race.

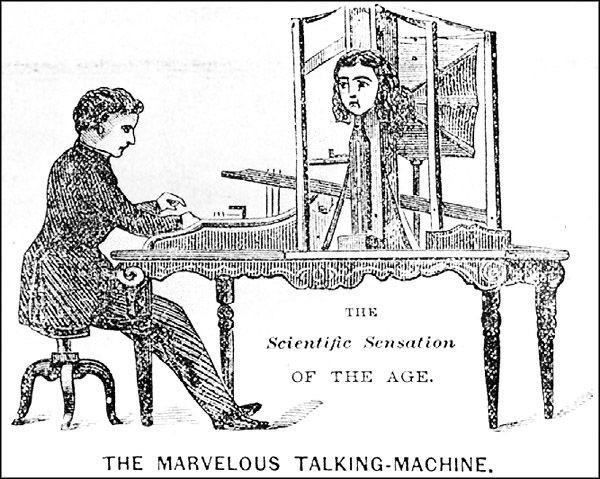

Joseph Faber’s Talking Machine

This bizarre-looking talking head spoke in a “weird, ghostly monotone” as Faber manipulated it with foot pedals and a keyboard.

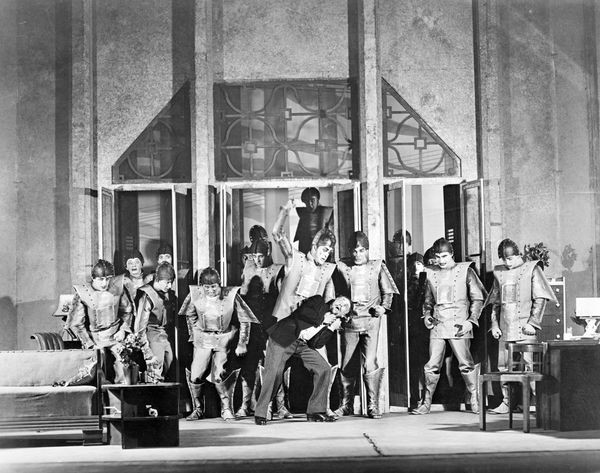

View Artifact DetailRobot Rebellion scene from R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

Damon, the play’s robot leader, says, “to be like people, it is necessary to kill and to dominate.”

View Artifact DetailCover of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

The play, quickly translated into English, provoked much discussion about robots. But Čapek said, “I was much more interested in men than in Robots.”

View Artifact Detail